Anatomy of a Train Wreck: The Rise and Fall of Priming Research Ruth Leys Univ. Chicago Press (2024)

In 1996, psychologists reported that people walk more slowly after reading words associated with ageing, such as ‘grey’ and ‘old’. This delightfully unexpected finding — an example of a phenomenon called social priming, in which stimuli such as meaningful words unconsciously influence behaviour — became one of the most influential results in the field of social psychology (J. A. Bargh et al. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 71, 230–244; 1996).

It also heralded a reproducibility crisis. In 2012, another team of psychologists reported that it had tried and failed to replicate the result. Despite a vigorous defence of the original study in now-deleted blogposts by its lead author, John Bargh, most psychologists have since concluded that what they came to call the elderly effect is probably not real. As other results in the field also toppled, the crisis stimulated fierce debate about how to study the ways in which humans think and behave.

What’s next for psychology’s embattled field of social priming

This revealing episode is the subject of Anatomy of a Train Wreck, in which historian of science Ruth Leys asks how a supposed breakthrough in a provocative and influential research field turned out, ultimately, to be a cautionary tale. Packed with compelling research, her engaging account will be of interest to anyone curious about psychology and influences on human behaviour.

Leys begins by examining one of the dominant strands of social psychology in the 1970s and 80s, attribution research. Investigations of how people understand their own and others’ behaviours, as the result of either one’s character or of circumstances, suggested that people are sometimes ignorant of why they take the actions that they do. For instance, people tend to make up explanations — insisting, say, that they chose one of two identical objects because they had ‘noticed’ that one was of higher quality.

This work laid the foundations for theories of social priming by seeming to show that actions are not — or at least, not always — the product of conscious decision-making, but can be the result of unconscious processes.

Conforming to expectations

Leys then carefully recounts social priming’s troubles. Critics argued that the elderly effect was a consequence of participants conforming to experimenters’ expectations about how they would behave, rather than responding to the cue words alone. Avoiding inadvertently influencing participants is a familiar methodological difficulty in psychology experiments, which Bargh insisted his team had addressed. Nonetheless, repeated attempts to replicate the finding failed. So did efforts to replicate many other examples of social priming — such as the ‘professor effect’, in which thinking of a professor while taking a test supposedly improves results.

Replication games: how to make reproducibility research more systematic

Leys goes beyond this history to question theories that underpin the fields of social psychology and cognitive science. Her critique is influenced by the philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe’s classic work on the theory of human action, Intention (1957). Like Anscombe, Leys highlights the difference between reasons and causes when it comes to explaining and justifying actions.

Behaviours make sense in light of people’s reasons — they might buy ice cream because they want to eat ice cream, for instance. By contrast, actions needn’t make sense in light of causes — someone could buy ice cream because they are hypnotized, say, regardless of their wants and needs. Leys argues that many social psychologists, including Bargh, have missed this difference; they focus exclusively on the causes of actions and ignore people’s reasons. And, she continues, social-priming experiments fail to replicate, in part, because people always have unique reasons for their actions, which depend on their individual histories. For instance, she suggests, whether people walk more slowly when they read a word such as ‘old’ depends on what they want and believe: after all, they could equally well walk faster to help an old person.

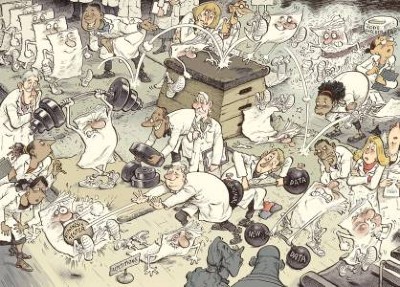

A person’s behaviour is shaped by context.Credit: Getty